It’s not just the port work alone that creates spectacular cylinder head performance. The most critical areas of a cylinder head are those which pass the most air at the highest speed and for the longest duration. Your bowl area, the valve job, the throat diameter, and combustion chamber are all crucial parts.

Every engine builder is after the ultimate in performance gains. When it comes to cylinder head performance, we’re all trying to maximize airflow to create more power. In order to accomplish that, builders have to know what to manipulate in order to make improvements. Those improvements to airflow quality and quantity come from porting and removing areas of restriction.

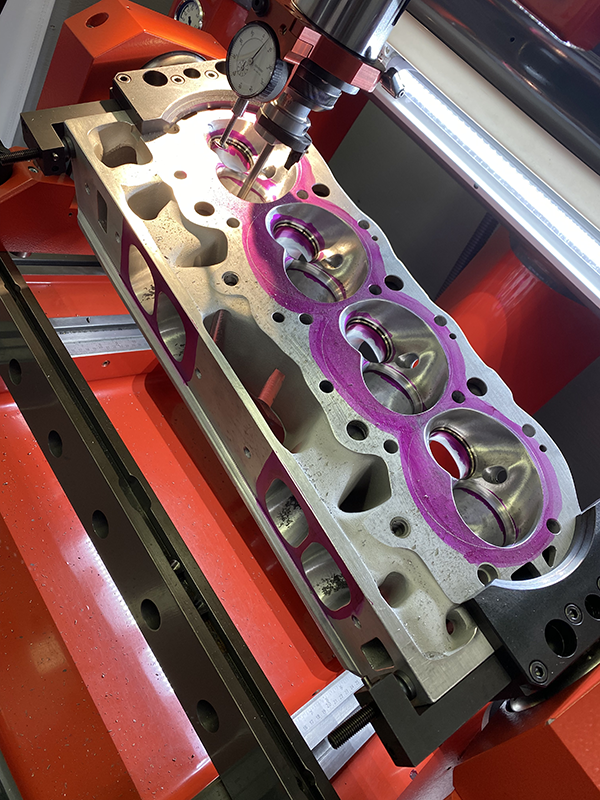

Since every cylinder head is different, learning how to improve airflow characteristics involves a lot of trial and error and many hours on the flow bench. A skilled cylinder head specialist will focus on shaping the port to get the maximum flow with the minimal amount of enlargement so that maximum intake and exhaust air speed is maintained. Specialists are also trying to achieve equal flow through each port, so each cylinder experiences a similar air speed.

Well-performing cylinder heads that produce good airflow typically start with a well-done valve job.

No matter whether a cylinder head is for a forced induction application or naturally aspirated, performance gains can be made through port work, and these days, CNC porting has become an affordable, quicker option over hand porting.

“Doing a port, getting one right by spending time and making it perfect, then digitizing, that’s the way to go,” says Carmen Trischitta of CT Performance Machine. “Sitting there by hand, trying to get two cylinder heads done and running through eight ports – that’s too much work. In today’s day and age, it’s kind of stupid if you ask me. Get one done and let the machine do it for you.”

The benefits of the CNC approach are accuracy, repeatability and speed. However, a CNC-ported head doesn’t have to be, and in many cases, shouldn’t be, the end of the road. Skilled engine builders and cylinder head specialists can further improve CNC’d ports to really create something special for the end customer.

“I thank cylinder head companies like Frankenstein and Advanced Induction for getting me close and then I’m taking it to the next level,” Trischitta says. “The way I go about it is I look inside that hole and I think about if I were the air and the fuel mixture running through this port, what am I not going to like as I’m going through it. Then, I tailor the port through my vision of the path that air and fuel mixture is going to take.”

It’s not just the port work alone that creates spectacular cylinder head performance. The most critical areas of a cylinder head are those which pass the most air at the highest speed and for the longest duration. Your bowl area, the valve job, the throat diameter, and combustion chamber are all crucial parts.

“Porting is only a part of the whole equation of the whole recipe,” Trischitta says. “It’s the combustion chamber. It’s seat angles. It’s above and below the seat. It’s at the flange of the intake. It’s through the intake to the throttle body or carburetor. It’s adapting it all.”

When working on a cylinder head port, you’re trying to create a venturi, which can be created by hand or through the use of CNC machining. However, you may have noticed CNC work often has one drawback.

“Using the CNC is great, but often times you can see the tooling lines, which give it a washboard effect,” Trischitta says. “Some CNCs do a better job than others with that, but it’s still getting you an even port across the board. From there, you can hand tailor it.”

Carmen’s shop, CT Performance Machine is a low-volume engine shop, so he has the ability to perform finish work by hand to provide a very customized cylinder head. Other shops that are higher volume likely have to rely on the CNC work alone, and with today’s equipment, you’re not losing much going that route.

Different carbide burrs and cartridge rolls are used to achieve various finishes within a cylinder head port. The abrasive and the head speed also factor into how material gets removed.

“A lot of these cylinder head companies produce a really great component that will flow good air as is, but they also appreciate a nice finish job that goes that extra mile,” he says. “Guys who are cranking out engine after engine after engine, they’re not going to sit there and do that kind of hand porting work. Me, I’m not that high of volume, I’m lower volume, so every piece that I do, I’m going to go through it from top to bottom as best as I can get it. I’m going to put all that effort into it, starting from the flange, the combustion chamber, all the way up to the valve seat, all the way up the port, and then make sure that intake is matching.”

When chasing that last bit of efficiency, factors including the shape, cross section, surface finish and overall volume of the ports come into play. Larger volume ports may seem like a good idea, but more volume can often mean losing torque due to lower air/fuel velocity, especially at lower engine speeds. If taken too far, volume increases can even lead to airflow reversion or backup, where air literally backs out of the combustion chamber towards the intake manifold.

Through the use of a flow bench, you can hear whether or not you have a good port during testing. It’ll start spitting and sputtering if the air can’t make the turn to the valve, which is a result of air speed being too fast.

By using a probe, you can determine where the port is too fast at. Is it too fast in front of the turn? Is it too fast over on the side of the turn? Is it too fast around the pushrod pinch area? That’s where it comes down to tuning a port up nicely and making it run well.

Cylinder head porting is something that you develop with repetition. You make subtle changes and you see if it makes it better or made it worse. Air has to pass like a funnel effect. It starts bigger in the front and as you get towards the valve, the port gets smaller and smaller. Ideally, your throat area or your seat ring, would be the smallest spot in the complete port. Straightening the ports while increasing volume as little as possible is therefore the most common approach.

CNC-ported heads produce great results these days, but a hand-finished port can go that extra mile.

“When I’m envisioning what the air won’t like, that’s how I see those bumps to blend in and get out of the way,” Trischitta says. “I’ll try to ramp it in and get the air around the guide. When the air comes around the back of the guide, hits the back of the port and then wants to come out the valve – you want that air. It helps to think about it like a wind tunnel, and how one little change of a spoiler deflects air into a whole different path. I’m trying to deflect the air and get it to where it’s got to go – around that valve.”

Something Carmen also always does on his engine builds is port matches the cylinder head to the intake manifold. This helps maximize the efficiency of all that air you’re trying to cram into the engine.

“Every intake on an engine I build is custom tailored to whatever cylinder head it’s sitting on,” Trischitta says. “The intake runner in the manifold is just the extension of the runner of the cylinder head. Imagine that you’ve got this head and it’s flowing 450-480 cfm on a flow bench. What happens when you put an intake manifold on it and the runner isn’t matched to the port of the cylinder head? You kill it! If you’re going to go into your cylinder heads, one of the most important things is to top it with the proper intake manifold and match that port. You’re trying to get the port and the flange to match up.”

No matter what sort of port work you’re performing, the number one thing to keep in mind is that hand porting is about patience. Always start on the small side and go bigger if you need to. If you start conservatively with the amount of material you remove, you will avoid a number of potential issues.

However, not everyone ends up being conservative, and the last thing you want to do is blast through into a water passage and have to get the head repaired or toss it in the garbage. Unfortunately, throat size is something people often do incorrectly, and how big or small it should be depends on the seat angle of your valve job. Again, you’re always better to run too small of a throat than too big of one.

It never hurts to envision the cylinder head port as a wind tunnel to help you understand where and how the air needs to travel.

“Those angles are there on the valve job to help that air turn,” he says. “If they’re not there anymore, it’s counterintuitive to what you did in the valve job. There are so many areas in the cylinder head you can really mess up on, but that’s probably the biggest one is the valve job and the transition into the throat area.”

Also don’t forget that the intake port works completely different than the exhaust. With the exhaust port, as long as it’s sized properly, you just want to make it as straight as possible. Once you have a head done, utilize the flow bench to check air speed and cfm. Air speed, according to most, is more important than cfm, despite what some folks might think or make purchasing decisions off of. If you get a cylinder head that has the appropriate air speed for what you’re doing, the port’s going to flow a lot of air.

“The flow bench is just going to give you numbers and let you know which direction you’re going,” Trischitta says. “We don’t race flow benches.”

It’s the bowl area and the short turn radius on the port floor that are critical to airflow in most cylinder heads. This is also the area of the head where porting experience comes into play, since changing the radius of the short turn and the overall shapes within the bowl area can have a big impact on the angle the airflow enters the combustion chamber at, which can in turn have a big impact on the combustion event itself.

If you’re looking to gain an advantage on your competition at the track, cylinder head porting should be a high priority. Whether you utilize the CNC route, or go a step further by finishing a port by hand, better engines and better performance will come of it. EB